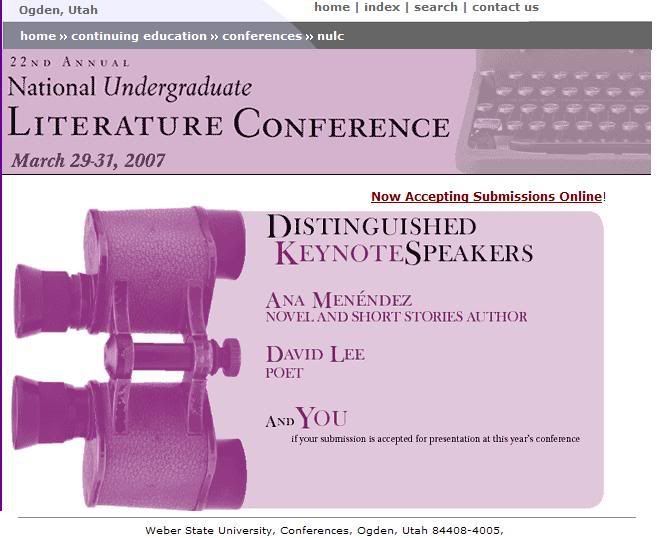

I submitted this story for the National Undergraduate Literature Conference. I might try to go even if it doesn't get accepted.

Bob and I had driven all day through the water. Passed with the secure herd of a few other tail-lights and destinations down into scummy, ankle-high brine. Watched the others, no turn signals or roadside signs to warn us, pull off onto higher-ground or make U-turns with spraying rooster tails. Bob and I moved like the water; naturally and bound by the same hills. When twilight became actual darkness we were alone with the whooshing beneath us and the disorientation of our headlights beaming out over the reflection.

I sort of dozed. Considered the rumor that if we kept moving there was a place we could catch a plane. Outside the window, the black was monolithic and our tired car threw meager light on the mystery as it passed. Bob, moaning in a way I'd learned was the wrath of delirium tremens, abruptly stopped and swung the door open. He stood in the metallic ding of the running car for a moment, waiting, and finally hurled the last few slugs of dried bagel in his stomach. The water at his feet gushed forward from our momentum and little whirlpools of salt-water and vomit spun around his pant-legs.

Somewhere around halfway, we saw the neon smudge of civilization ahead and sighed. The white rip of knuckles on Bob's left hand relaxed and moved to rub his forehead. When it appeared, like a nocturnal oasis, I couldn't determine whether it was a metropolis or the lonely campsite of some fellow travelers. We drove for twenty minutes. The glow was a lonely place called Ciro's; the name written in flickering, cursive red. It was a diner, familiar-looking, perched some thirty feet above the road. He wheeled the car into the sloping parking lot without conversation.

There was one customer sitting at the grubby counter, pensively shoveling apple pie into his mouth with one hand and stuttering a drum solo with the fingers of the other. A ruddy-faced waitress, uniformed in a puke green number with black trim, said something to him that thinly veiled her disgust. “Is that all your gonna eat?”

She turned to us, practically a girl, and asked in her twang if she could “ha'p” us.

We took seats at the counter, at Bob's gesture, and exchanged experienced hellos with the character. His clothes were shabby, not unlike our own, and his sloppy hat announced that “You Can Take This Job and Shove It”. Amber (from her nametag) brought us coffee and a nearly invisible cook in the place's nethers waved a spatula at us. It smelled like the docks.

“How much further is the water?” Bob asked, to everyone.

“Hell if I know,” our neighbor said “I been here almost 2 months now waiting for that damn Shevitz to pick my ass up”

“Who's Shevitz?” Bob asked.

“Shevitz is the son-of-a-bitch that stranded me out here in the friggin' ocean without a truck.” He replied and reached for a cigarette. His grip fierce on the soft-pack.

“Hardly answered the man's question, did'ja Tom?” Amber said, moving to fill our coffee cups, now emptied by one swallow.

“If you want to know how far the water goes to the south, truth is, I don't really know. It's been here, right in front of the diner, for a coup'a years now. But things change . . .”

“Does it get deeper?”

“Not too sure, this time of year. Depends on a lot of things . . .”

Bob and I ordered Bacon-Lettuce-Tomato sandwiches with french-fries, though I didn't know how we were going to pay for it or where they'd get the ingredients. The cook in the back, just white eyes buried in a brown face, looked delighted.

“I tell you what,” said Tom, “I'd be half-inclined go with you. But I don't know as I care a whit anymore.” He was smoking now.

“We've got to get to Marston.” I said, the first declarative out of my mouth in hours. I felt the twist of drying saliva in my throat, pulled my dingey hood up onto my head. “Trying to catch a plane.”

The cook in back laughed, and stopped himself on the heel of his palm. His eyes apologized.

“Don't know if that's going to happen . . not with what I've heard comin' outta Marston. . . You know,” Amber said. “A few months back, me and the cook tried to leave. . . “

They had pushed her moss-covered station wagon down to the road and crossed their fingers. The cook had taken the liberty to load everything up and when Amber had walked down from her shack in the hills he had simply pointed out toward the sunrise. Jabbing a few times for emphasis. The car had started with a cough and lurched out of park, but they were soon rolling through the brine.

They drove a few minutes, the slow progress we were now familiar with, until Amber felt a lightness in her chest. Ciro's now out of view, a looming uncertainty dangled like a carrot just out of reach. The hard part, leaving, was Amber's crux.

Maybe two miles to the north and east, the wagon, light on gas, began to sputter and burble black smoke from the partially submerged exhaust. The chattering idle sliding plastic debris and old paperwork off the dash. It finally grunted and stopped.

The cook, delirious in his frustration, had slammed the door shut behind him and ushered Amber up a few yards to higher ground. A breather before they headed back. The sun had fully risen and was now up over the hills. It was water and blank landscape from their feet to the horizon. Eventually they saw a splash, like a waterspout, breaking the surface out near the edge.

In a great slipping flail, Tom's truck had come in from the north, coming way too fast. He tried to brake and swerved, finally sliding to a stop only kicking distance from their car. Panicked and soaking, Tom leaned out the door with a desperate hello. His truck, too, was on its last legs. He didn't know where he was and needed their help.

“And so we're back here. With Tom.” Amber finished the story. She looked at Tom, absent-mindedly picking at his fingernail, and tried not to seethe. They had made no other attempts.

“Well, we've gotta try.” I said, “No other real options, the way Bob and I see it.”

Tom nodded his head, but debated whether to probe our intentions. We may be fugitives or refugees, he didn't care. He pulled at his beard a little bit.

“Worth a try, out on the coast you never know.” Tom said. He had settled a bit. This he said in my direction; almost warmly.

Bob became flush, his forehead now the tight wrinkles of a migraine. It had been a rough morning, followed by a trying day, and finally it seemed we might get some rest. He started to recall aloud the anxious nature of our drive, stopped short when he realized they knew the travails better than he and then winced and shielded his eyes from the fluorescent lights with his left hand.

“You alright?” Tom asked. I saw him saying the same thing to strung-out truckers in slimey South Dakota shower stalls.

“mkay. Just a little woozy. You,” He looked at Amber, cupping his left eye now like it had caught shrapnel. “Wouldn't happen to have any booze, would you?”

“Sorry,” she poured herself coffee, “Tom drank just about all of it in the first week. You need a drink that bad?”

“Yes.” I said, he'd be embarrassed to say it himself.

Bob was now rolling his forehead on the cold metal trim around the counter. A dull grunt and the word “ . . .libris”. Amber came around to our side of the counter, pulled up a chair to include the three of us, and took some items from her apron.

“You want to smoke some of this? Its not booze, but it might keep out the shakes.”

We did. And she broke up a cigarette and mixed a few pinches of brownish marijuana in. The cook gave a little exclamatory. The sizzle of bacon mingling with the pot and the dead fish smell of the sea.

“Frankly, since Tom. You boys are two of the only people we've seen . How many guys came in here the other night Tom?” She began, as though we'd provoked her.

“”s about a week ago Amber, or more. There was three of 'em. Sons of bitches.” Tom had now peeled the hat from his sweaty baldness and swiveled his chair around to point his crotch at Amber's head.

Bob moved to scrape a chair across the dirty floor; you could see where Amber had stopped mopping arm's reach from the counter. And the cook, a Peruvian I think, walked out with an identical plate in each hand and set them near us. He pulled a chair around to get a seat inside the circle and Amber lit her pregnant joint and thanked the cook in two languages. The power winked out and wound back up. Bob eyed his sandwich and later he would tell me that he saw maggots writhing inside of it and didn't know if they were real or he was dead. He waited for me to take a bite and dry-heaved once sharply.

Respite often leads perspective by the ear; and as I ate the day's first meal the impetus for all this dragging ourselves along and Bob's puking his brains out coalesced in my stomach. A warm ball of purpose. As serious as the will to live.

“C'mon Bob, you've got to eat this. You need something on your stomach.” Amber said. She briefly held his plate off the table, and wafted it under his nose. She started to pick up a sandwich half to feed to him.

“He going to be alright?” Tom asked me, finding something finally interesting after a long stretch of the same.

“I'll be fine,” Bob said. “It comes in waves, and builds... I'm going to lay on the floor.” He exhaled and raised the spliff for anyone to grab, purposely avoiding eye contact that might terrify him. When he landed on the ground, not delicately but with an “umph”, his head left a sweaty print with the texture of his hair.

“What's it like?” Amber asked. She skooched to the end of her chair and looked down on him. Her legs were crossed, the one on top bounced delicately. “Describe it.”

“He's really better at that sort of thing,” Bob looked at me with one eye, and then back toward the floor. “But it's . .uhh . . the worst hangover ever. And you see things that make your . . that seem more real than being awake.”

“What are you seeing right now?” Amber asked, the tail end of a hit.

“I'm seein' . . .I'm surrounded by pigeons, and they're mouthing my childhood nickname.”

“Dios mio,” said the cook.

Tom looked around for pigeons and took a great toke that ended in coughing; the sort of disturbing wet whoop that sounds like something dislodging deep inside. I ate the crust of my sandwich. Us three men tried to ignore Bob, me in the understanding that it would run its course and them in patent inability to pay attention or understand. Amber, though, was enraptured. She pushed herself closer and offered assistance should he need to puke again. No thanks the nausea was gone, but a moist towel would help. And when she returned and placed it on the back of his neck she looked up as though she remembered something.

“What's that?” she said pointing out the window and down to the road.

We all hustled over and pressed up against the glass, except for Bob, and saw a crude flotilla (illuminated only by the orange of its own torch) bobbing and drifting down the road in the direction we traveled. They'd lashed together crates and scrap styrofoam and used long poles to push themselves along or threaten each other. The craft dragged its belly across the ground six inches beneath surface.

The figures urging it ahead were tall and angular; disfigured in a way I recognized from home. It was drugs, people said. Or radiation sickness. Or some genetic malady from the intersection of the two. One looked up into the diner and Tom nearly gasped; it had a low brow and pointed awkwardly up to us. The mouth hung open as though to yell, but the thing on the float merely stood slack-jawed as it passed.

Nothing to say. We watched until their torchlight veered around a curve and cast their long, frantic shadows back on the water behind them. They had moved on. We shrugged and shuffled back to the ring of chairs.

Bob moaned a little tiny moan: “The whole room bathed in laboratory green, enormous roots pushing up the tile . . . .”

Now he'd acclimated to the trauma enough to sit back upright in his chair; looking ten years older than he did ten minutes prior. He squared his shoulders and pointed his knees in; contorting into a stiff symmetry only to be loosened and disordered by tremors.

“In the interest of keeping you updated,” he said. There was something between frustration and awe in his twitching left eye. “We are as on a precipice. Parched by the desert sun.”

“I could do without that,” Tom said to me as though I'd be on his side for this, “Guy is sick as a dog, he should go lay down.”

We considered that. It might tack hours back onto Bob's lifespan.

“I'll lay down when we get to Marston,” he finally said.

“Where are you coming from, anyway?” Tom asked, waving the answer out of us with a hand motion and a dismissive tone. As though we should have already clearly stated our itinerary.

“We're coming from the place we grew up. You'd never of heard of it. Things are kind of over there . . .” Tom flashed me the profile of his face, and looked down at the moldy tile. Amber's leg restarted its bounce, more nerves this time. And the cook sighed heavily.

“Things are kind of over here too,” she said.

“We're going to die in this hole, Amber. I told you.” Tom said. “I spent my whole goddamned life driving truck and trying to . . here I am dying with people I don't even know.”

The food eaten, the spliff all but gone and the coffee waning.

“What's going on in there now?” Amber asked. Snuffing out the roach and pushing the ashtray from her like she had nothing to do with it. She leaned in studiously on her elbow.

“You're in flowing velvet.” He gulped at his outrageous claim. “There are dozens of. . .umm . . .Lilliputians. They're beaming at you in admiration. There are dozens of them, running up and down you. Pinning something up. Pampering you.”

“You don't say.” Amber said, she picked at a loose thread.

At no behest, the Peruvian fetched more coffee. He seemed to sit apart from the comfortable quiet the rest of us had taken on. I don't know how much he understood, but as he poured my cup he stammered something exhausted about “trying to make her leave” and shook his head from side to side. How could there still be coffee at this rate?

Amber had dropped her waitress duties and flattened her skirt across her lap, inviting Lilliputians up onto her hand and looking to Bob for encouragement. No TV, no radio. Just Tom and a silent guardian for months. Tom who now ranted to me on his string of rotten luck; his various dying relatives and friends, now almost unfamiliar. The boss who had marooned him in a strange place. The god that had booby-trapped reality.

“And I just now realize. It just now really hit me . . .we're going to die here. And there isn't a thing I can do about it.”

“You.” Bob said and pointed at the Peruvian “You are a foundation. Chiseled out of rock, the building moves not you.”

“I've been saying that since I met him!” Amber said, a little squeal of recognition. “Poor guy doesn't have the foggiest what we're saying. Just mopes around here all day. Pushing us outside to have a look at things.”

“His arms are like tremendous cactii . . swollen, tumorous.” Bob went on. “Amber, can you get me something to throw this sandwich up in?” It was almost procedural now, like patiently enduring as a doctor burns off leeches or leverages out bullets with a sharp point. I don't know where the line is between what he's actually seeing and his imagination.

“What are you boys going to do?” Tom asked me.

“I'm not quite sure,” I said. Bristling honesty, a little acorn rose in my throat at actually hearing the starkness of our plan. “I think we're going to see the world.”

“Ha!” Tom yelled, he slapped his knee. “You hear that Amber!?”

“Tom.” Bob said, “You are an assemblage of machinery. A conveyor belt, no physics, rolls in a big loop around you . ...” Bob made a circular motion with his finger in the air, at arms length. Once. Twice with a whooshing sound. “Your body parts are components, constantly being worked on by tools suspended from the ceiling. They move around your body. Its a process. Now your leg is 4 feet off the ground, spinning on a lathe. God, I can hear the servos whirring.”

“What is he talking about?” Tom asked. He looked sidelong at Bob. “Shut up, wouldja?”

“You can only talk when your head is in the right position, its being bolted at shoulder height now . . try to talk.” Bob said.

“. . . .” He was taken aback. He couldn't speak.

“And?”

“ . . .” then finally “Amber, what is this all about?”

“You see? Couldn't speak until the alignment was right.”

Tom was ruffled. His eyes darted from me to Bob to Amber. He stood up from his chair and leaned on the back. There was the briefest tension and I wasn't sure whether Bob was making a point. Tom's expression soured like a convict's sudden remorse when he hears the verdict. And he started to slowly back towards the dirty corner booth he must have slept in each night.

“What, what are we hav-having for breakfast tomorrow, Amber?” he stuttered.

“We'll have some oatmeal, don't you worry.”

“Good night then.”

“The three of you,” Bob cleared his throat. Carefully chose his words. “The three of you are a jumble of sticks. One can't be moved without it falling apart.”

“I think you need some rest my friend.” And Tom finally turned.

“Why do you stay here?” I asked Amber. She looked over her shoulder before she would answer.

The cook ducked before the window broke and, apparently on instincts, jumped out of the way of the cinder-block in the instant before it crashed into the tile floor. One of the degenerate sailors from what seemed like hours ago stuck his massive head through the narrow hole the brick left and smiled droolingly at us. He pulled back and kicked the rest of the glass in with his bare foot. They were laying siege.

As they poured in, we froze. Maybe they couldn't see us if we didn't move. There were four of them and when they collected themselves inside the diner one smelled the air and made a little grunt. Another stamped his foot. They were dressed in scraps of clothing, mauved by sunlight. And their deeply tanned torsos displayed illiterate smears of grease for warpaint. One had pointy ears, another's eyes bulged and disordered. The leader, his foot now bleeding from the kick to the unlocked door, gnashed a shattered row of teeth.

Tom broke first. Furthest from the door he sprinted towards the kitchen. In a mammalian flinch one of the invaders flung his rough-hewn spear in the space between the rest of us. Tom, impaled, fell onto a table then the floor. Excitement boiled over, and if he had been alone I think they would have broke into ritualistic dance. One slapped the killer on the back. The cook, forearms bristling, effortlessly heaved our table into the gang's tight bunch and pointed at the door. Amber, Bob, me. We flowed out the door like a swell of birds; briefly one mind and the relief she felt upon fresh air was only dampened by the terror in one last look before she lunged into our car.

»» read more